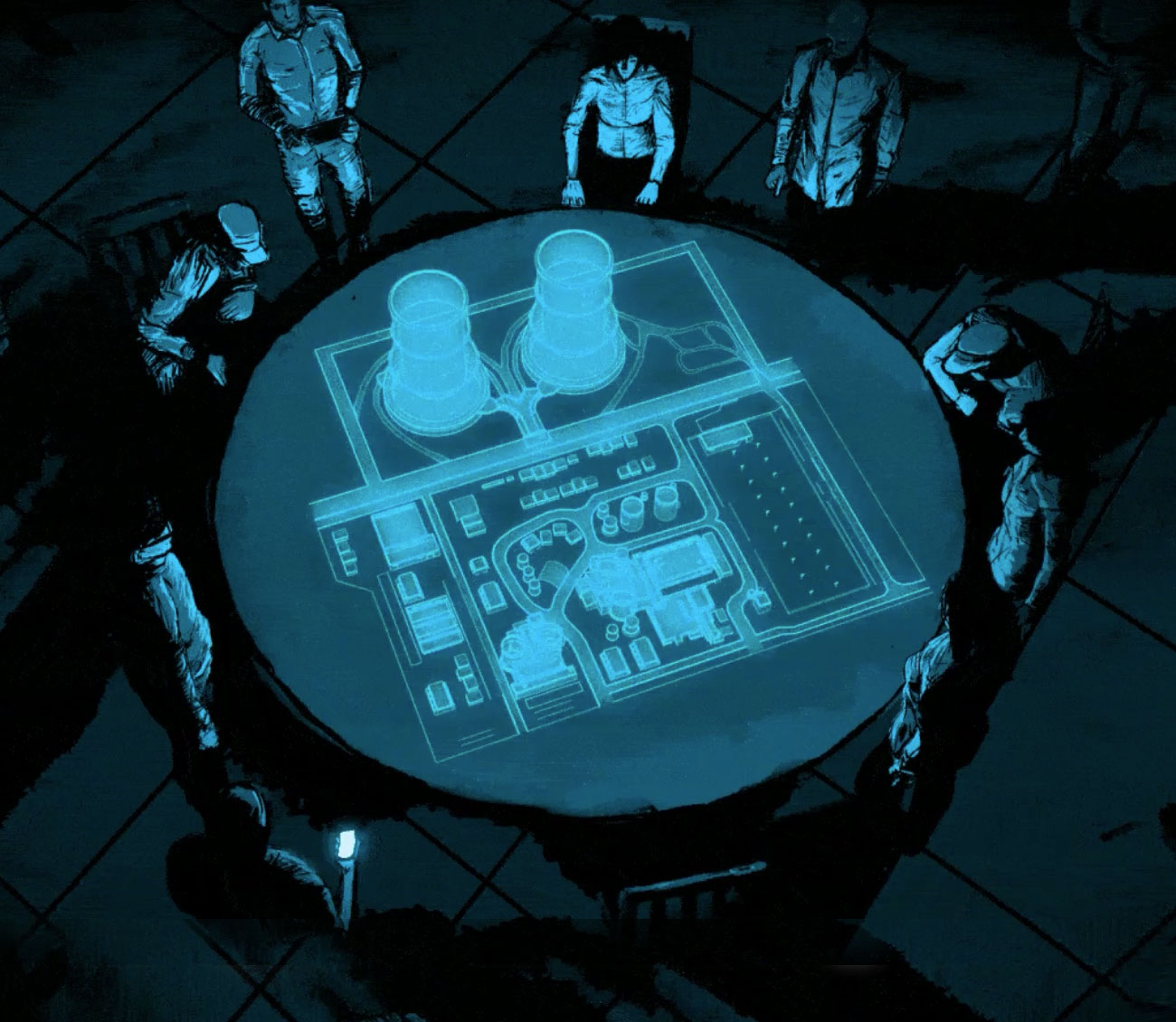

Nightmare scenario

By Sean Lyngaas January 23, 2018, Illustrations by Alex Castro and William Joel

The nuclear plant employees stood in rain boots in a pool of water, sizing up the damage. Mopping up the floor would be straightforward, but cleaning up the digital mess would be far from it.

A hacker in an adjacent room had hijacked a simulated power plant, using the industrial controls against themselves to flood the cooling system.

It took officials from three different Swedish nuclear plants, who were brought in to defend against an array of cyberattacks, a couple of hours to disconnect the industrial computer (known as a programmable logic controller) running the system and coordinate its repair.

Though the exercise was conducted in a simulated coal plant, not a nuclear one, the tactile nature of the demonstration — the act of donning rubber boots to fix the flooding — drove home the potential physical consequence of a cyberattack on critical infrastructure. “The next step for them is to go back home and train in their real environment,” Erik Biverot, a former lieutenant colonel in the Swedish army who planned the event, told The Verge.

The drill, which took place this past October at a research facility 110 miles southwest of Stockholm, was the most technically sophisticated cyber exercise in which the UN’s nuclear watchdog — the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) — has participated.

“The next step for them is to go back home and train in their real environment.”

Security experts say more of these hands-on demonstrations are needed to get an industry traditionally focused on physical protection to think more creatively about growing cyber threats. The extent to which their advice is heeded will determine how prepared nuclear facilities are for the next attack.

“Unless we start to think more creatively, more inclusively, and have cross-functional thinking going into this, we’re going to stay with a very old-fashioned [security] model which I think is potentially vulnerable,” said Roger Howsley, executive director of the World Institute for Nuclear Security (WINS).

The stakes are high for this multibillion-dollar sector: a cyberattack combined with a physical one could, in theory, lead to the release of radiation or the theft of fissile material. However remote the possibility, the nuclear industry doesn’t have the luxury of banking on probabilities. And even a minor attack on a plant’s IT systems could further erode public confidence in nuclear power. It is this cruelly small room for error that motivates some in the industry to imagine what, until fairly recently, was unimaginable.

Read more here